Crescent and Longfellow

Introduction

With the introduction of more and more governmental electronic identities (e-ID) in the EU and Switzerland, the question of privacy becomes ever more important. We wrote an Overview of Privacy and Unlinkability1 where we give a list of the most important elements to consider with regards to this topic. In this blog post we look at the Zero Knowledge Proof as mitigation for a majority of attacks described in the Overview post. We specifically focus on two papers published in 2025, which both take into account the following constraints:

- Optimise the prover time: for e-ID system, the holder of the credential usually has a mobile phone with restricted computing capabilities

- Include a ZKP of an ECDSA signature from a secp256r1 key: this is needed to proof the issuance. For holder binding, the signature must also be verified without disclosing the public key of the device.

- Work with existing credentials: use SD-JWT or mDoc as credentials, even though they are not optimized for ZKPs, contrary to BBS.

The papers we present in this post are the following:

- Crescent2, by Christian Paquin, Guru-Vamsi Policharla, and Greg Zaverucha - Microsoft

- Longfellow3, by Matteo Frigo and abhi shelat - Google

Crescent breakdown

Crescent2 is built in a modular way using Groth164, sigma-proofs[^sigma-proofs], and Spartan5 a construction authored by Srinath Setty also at Microsoft Research. The paper focuses on presenting SD-JWT6 credentials and publishes performance benchmarks to present SD-JWTs with and without disclosures, with and without holder binding, as well as the presentation of an mDL7 (without disclosures or holder binding).

Security assumptions

Groth16 requires a trusted public setup per-circuit and builds on bilinear pairings of elliptic curves. The security assumptions inherited from its construction are:

- Knowledge of exponents,

- and q-power Diffie-Hellman, two non-standard but falsifiable assumptions.

Spartan can be instantiated for different models. Crescent uses the discrete logarithm variant, relying on the hardness of the DLP. The paper specifically instantiates Spartan5 for the Tom-256 curve8 to ensure good performance of the ECDSA verification algorithm.

Construction

At a very high level, presenting a credential in Crescent requires:

- a pre-computation step that produces a Groth164 proof (Section 3.2),

- a

showproof that re-randomizes the Groth16 proof, produces commitments to attributes if necessary and a sigma proof to tie them to the main Groth16 proof (Section 3.3) - an optional linking proof, if holder binding is required, that uses Spartan5 with Tom-2568 to prove the ability of the holder to produce signatures that match the device key embedded in the shown credential (Section 3.4).

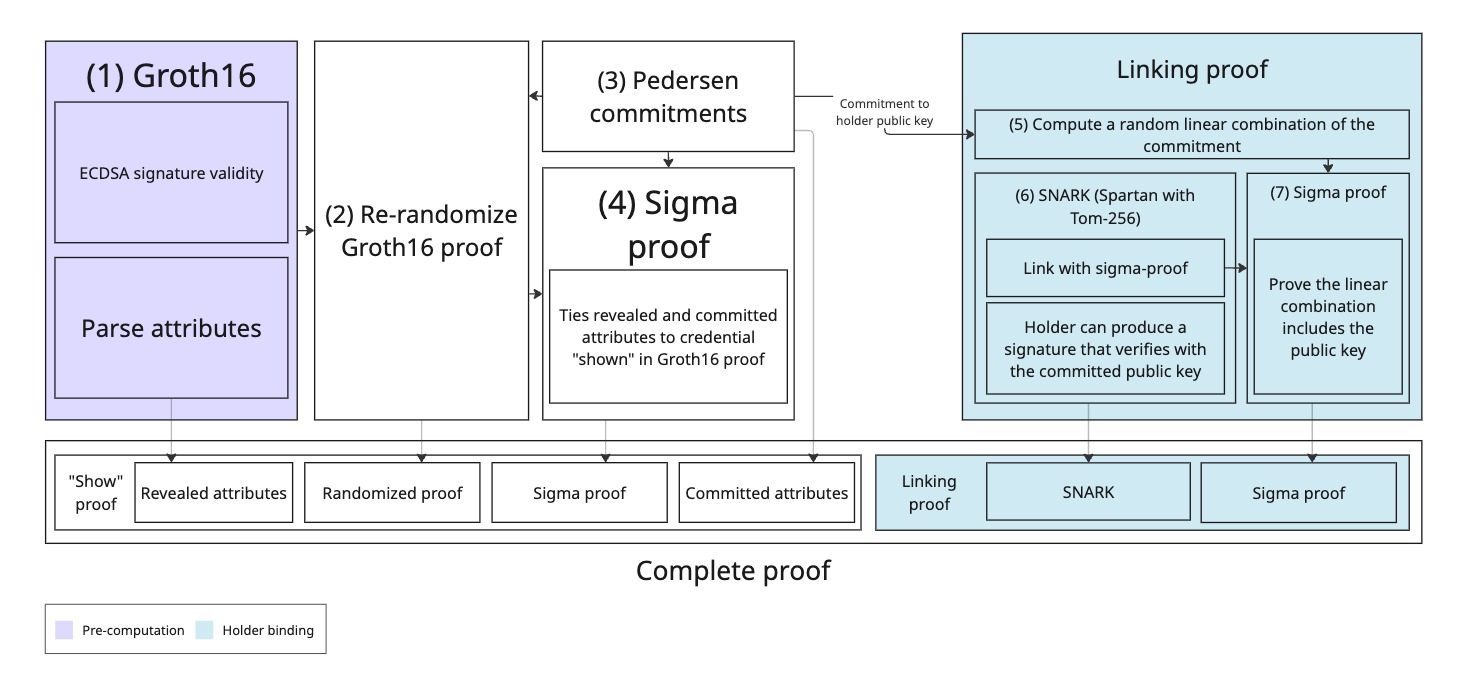

A block diagram of the components in a Crescent proof. On the left: the main proof of the credential validity. On the right: the linking proof, demonstrating that the holder knows the private key corresponding to the public key bound in the credential.

A block diagram of the components in a Crescent proof. On the left: the main proof of the credential validity. On the right: the linking proof, demonstrating that the holder knows the private key corresponding to the public key bound in the credential.

Credential validity and attributes disclosure

The validity of the credential is proven by the holder using Groth16 and a circuit that outputs the parsed attributes of the credential. Due to the time and memory cost incurred by the prover (more on that later), this step is pre-computed (Section 3.2). To ensure the freshness of the proof, and therefore prevent linkability of the prover, the Groth16 proof is re-randomized for each presentation. (Section 3.3, Step 2 of “Show”)

Each attribute can be either hidden, committed to, or revealed during a presentation. The holder uses Pedersen commitments[^pedersen] to commit to attributes. (Section 3.3, Step 3 of “Show”) The validity of the credential and the disclosed and committed attributes are then tied together with a sigma-proof. (Section 3.3, Step 4 of “Show”)

Linking proof

When holder binding is a requirement, the holder needs to prove it is able to produce a signature with the private key matching the public key embedded in the presented credential. This, again, needs to be fresh for each presentation to prevent linkability. (Section 3.4)

To achieve this, the “linker” (author’s terminology) rely on the fact that the validity proof can output commitment to attributes. In particular, it uses a commitment to the public key of the holder. It then proves with a SNARK that it can sign a message such that the committed public key correctly verifies the signature. (Section 3.4.1, Step 5 of the linking proof) The commitment to the public key is blinded using a random linear combination, and a sigma-proof proves the committed key is the one used for the verification algorithm in the SNARK. (Section 3.4.1, Step 3 and 4 of linking proof) The linker uses Spartan5 with Tom-256, a SNARK that does not require a public setup. (Section 3.4.1, “ECDSA Signature Proof”)

Available code

The publication comes with a proof-of-concept public repository: crescent-credentials repository2 (no maintenance as of November 2025).

Most of the code is written in Rust. Circuits are written using circom.

Takeaways

As in longfellow-zk3, the parsing of the credential is the largest cost to the prover.

The pre-computation of the Groth16 proof is the only way to make this construction usable. The pre-computation (performed only once per credential) costs:

- 593 MB and 20s for an SD-JWT without holder binding or disclosure

- 1.1GB and 140s for an mDL without holder binding or disclosure

The benchmarks are reported as having been performed on an Intel Xeon W-2133 CPU @ 3.6 GHz – a workstation CPU, not a consumer phone one.

The fact that only the holder binding proof is performed using Spartan hints that, even with the Tom-256 curve, proving the validity of the credential with this construction would be too costly.

Longfellow breakdown

In November 2024, Matteo Frigo and abhi shelat published “Anonymous Credentials from ECDSA”3. The paper describes a construction used for zero-knowledge presentations of mDoc with extremely good times: 1.17s for the prover, 0.68s for the verifier on a Pixel 6 phone. In early 2025, Google releases a public repository with Longfellow-zk’s code3.

The Longfellow-zk construction does not require any public setup or pre-computation from either parties.

Security assumptions

Longfellow’s proposal builds on a combination of Sumcheck9 and Ligero10. As such, it relies on the Random Oracle Model11 and does not require a public setup. As a reminder, the assumption made by the Random Oracle Model is the existence of collision-resistant hash functions (Theorem 1.1 in Ligero’s paper10).

Construction

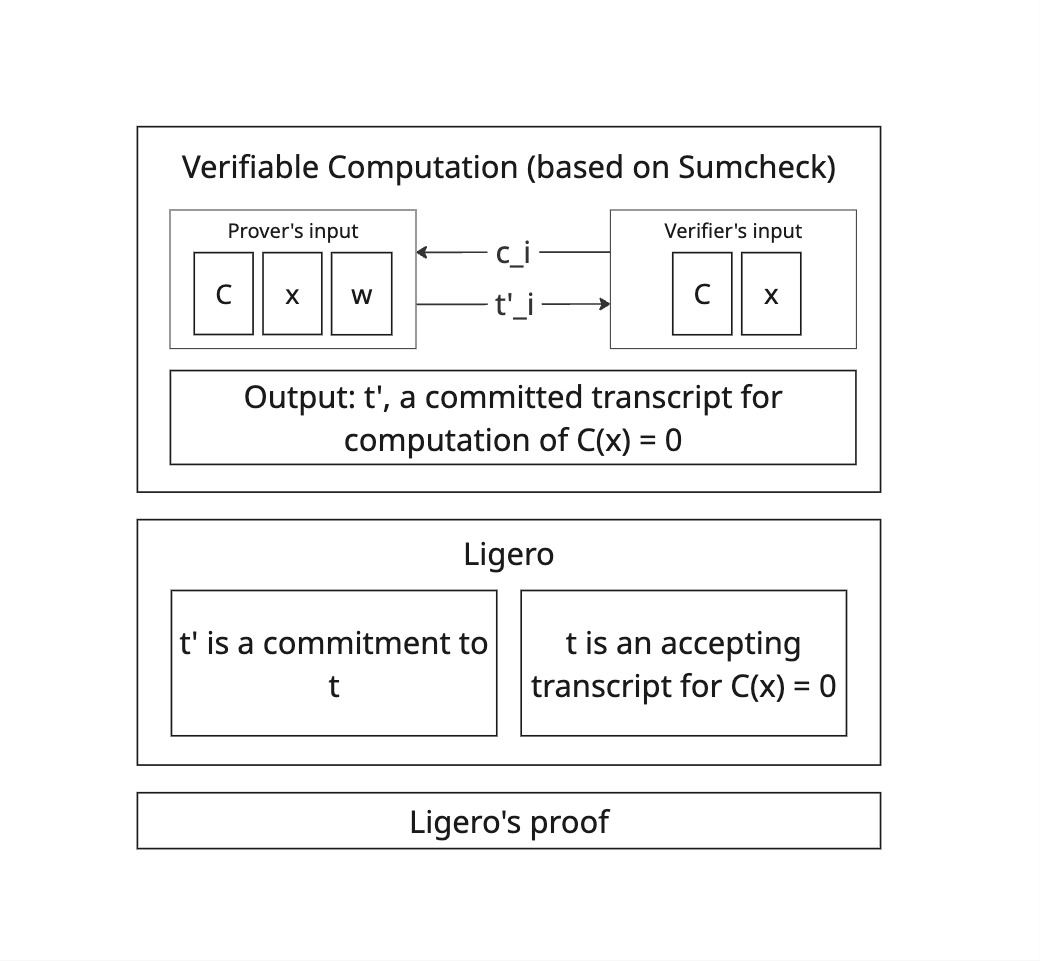

High-level overview of Longfellow-zk proof mechanism (described in the original paper, section 2).

High-level overview of Longfellow-zk proof mechanism (described in the original paper, section 2).

Instead of relying on a SNARK construction, Longfellow uses Ligero to prove the correctness of execution of a protocol that proves \(C(x) = 0\) for public circuit \(C\), public input \(x\), and private (prover) input \(w\).

Ligero is not used to prove \(C(x) = 0\) directly as the computation is large and performing NTT12 on such a large matrix would result in prohibitive proof generation time for the prover.

Instead, a variant of Sumcheck is designed and used for the prover to commit to an accepting transcript t and Ligero is used to prove that this committed transcript t’ corresponds to t and that t is indeed a proof that \(C(x) = 0\).

As \(|t| \lt |C|\), this results in much better performance. Section 5.2.1, page 37 describes the result of benchmarks for SHA-256 as “roughly 20x faster” than a Ligero instance.

Available code

Longfellow-zk repository3 hosts an implementation of the proof system along with circuits and benchmarks. A security review by Trailsofbits13 is available and high severity issues have been corrected.

Takeaways

Longfellow relies on a “simple” construction backed by less-accessible optimizations of the proving system and the circuits construction. For an mDoc credential, proving the issuer and holder signature, revocation check, and age proof, clocks in at 1.17s, while verification takes 0.68s on a Pixel 6 Pro phone (Section 6.2). This is achieved without any pre-computation, nor public setup. Unfortunately, the current open-source toolchain does not provide an easy way to write new circuits for other credential format or proof requests. Section 6.2 also explains that the largest portion of the computation cost is due to the credential format itself.

Comparison of Longfellow and Crescent

The following compares both algorithm with regards to their main aspects:

| Measure | Crescent | Longfellow |

|---|---|---|

| Technical | ||

| ZKPs used | Groth16, Spartan, Sigma proof | Ligero, Sumcheck |

| Post-quantum | No | Yes |

| Prover time | 30s + 1s | 1s |

| Verifier time | < 1s | < 1s |

| Proof size | up to 1GB trusted params + 15KB / credential | ~ 300 KB (For >60 attributes) |

| Implementations | ||

| Github (2025/11) | last commit: 2025/06 | last commit: 2025/11 |

| External Audit | No | Yes, available |

| Usability | Good documentation and sample application | |

| Composability | Possible, due to Pedersen vector commitments | Very difficult (tools not available) |

| Required expertise | High | Very high |

Longfellow has been written to be implemented in an application using user credentials in a banking app for Deutsche Bank14. For Crescent, there is no current usage documented yet.

From a performance point of view, Longfellow is superior to Crescent, as it can deliver a proof without having to perform lengthy pre-computation. On the other hand, Crescent has a more modular and understandable approach of creating the proofs and allow for other usages than the ones provided.

Both libraries suffer from the fact that they are hand-crafted for performance, and as such need a high confidence from the users. A more ideal solution would be based on a more understandable framework like Noir15, which lacks unfortunately the speed required for usage in mobile devices.

Suitability for Swiyu

Both Longfellow and Crescent provide an anonymous way of proving attributes of the users’ credentials. The Swiyu features that are relevant here are:

- Credential format: Swiyu uses SD-JWT VC

- Holder-binding: Swiyu requires holder binding with ECDSA on secp256r1

- Revocation: Currently, Swiyu has a status list implementation for revocation

- Identifier usage: Swiyu uses DID:webvh

- Communication protocol: OID4VP for the presentation of the credential to a third party. The OID4VP spec in Appendix B16 describes that OID4VP can transport any request and answer of presentation, as long as the sender and the receiver can use them.

Here is a short overview of both Longfellow and Crescent with regards to these features:

Longfellow

Longfellow concentrates on performance and works with the ISO mDL standard (ISO/IEC 18013-5). It uses standard ECDSA on secp256r1 as it’s chosen signature for both the issuer and the device signature.

- Credential formats: the ISO mDL format was picked as it’s one of the most used formats in the USA, and it’s also mandated in the EUDI specification in Europe.

A first implementation for JWT exists in the github repository17, but it is still work in progress as stated in the June ‘25’ review by dyne18…

As the Longfellow library already allows for selective disclosure, this implementation could be used, ignoring the

SDpart of SD-JWT. - Holder binding: the public key of the holder’s wallet must be added to the mDL document, and will be used to create the proof.

- Revocation: Swiyu uses Token Status Lists19 which was designed to work with the CBOR encoding used in mDL, so Longfellow would work seamlessly here as well.

- Identifier usage: Longfellow requires the public key of the issuer. However, it doesn’t require any specific standard for the format of the identity of the issuer or holder. Therefore, the choice of identifiers is not relevant as long as the identifier mechanism is able to provide the keys to the longfellow library when needed.

The biggest advantage of Longfellow is the very fast proving and verification time, which is less than 1 second on modern mobile phones. This makes it directly usable as a solution for verifying Swiyu credentials.

Crescent

The Microsoft Crescent solution sacrifices performance to provide a more generic proof framework, which is extensible more easily. The library they offer also provides more user-friendly instructions for running the library quickly, and easily integrate it.

- Credential formats: it supports both mDL and JWT and has an implementation for both of them.

- Holder binding: the proofs are created for the signature of the issuer, as well as a signature from the public key in the device on a challenge sent by the verifier.

- Revocation: Crescent paper never mentions revocation. However, we assume that standard Zero-knowledge Set membership techniques will still apply here. (Specially that Token Status Lists integrate natively with mdocs, and KWT)

- Identifier usage: the public key of the issuer must be provided to the proof, and can be taken from a DID:webvh.

The easy extensibility of Crescent comes with a price regarding the proof-creation:

- Pre-computation time: for every new credential added to the wallet, Crescent needs to do a once-per-credential setup which can take up to 26 seconds accordingly to microsoft’s benchmarks (in the case of JWT). However, this can be handled in the application background, and appear very smoothly using some UX optimizations.

- Per presentation time: 1 second

- Proof size: 40 KB per credential (precomputed proof) + 1~15 KB presentation proof (sent to the verifier)

- Trusted Parameters: the Zero-Knowledge protocol used in Crescent (Groth16) requires the use of a “trusted set of parameters” that can be generated by either distributed protocols between holders, and verifiers (which can be difficult due to the large number of holders and verifiers) or generated by a trusted third-party. The size of these parameters ranges between 500 MB and 1.1 GB.

It’s worth noting here that the trusted parameters can take a space up to 1 GB (or more). An E-ID system using Crescent will need to decide how to implement this trusted parameter setup.

References

-

Crescent: Stronger Privacy for Existing Credentials - https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/2013, code available here: https://github.com/microsoft/crescent-credentials ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Anonymous credentials from ECDSA - https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/2010, code available here: https://github.com/google/longfellow-zk ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Groth16 - https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/260 ↩ ↩2

-

Spartan - https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/550 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

SD-JWT - https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/draft-ietf-oauth-selective-disclosure-jwt/ ↩

-

Mobile Drivers License (mDL) - https://www.iso.org/standard/69084.html or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mobile_driver%27s_license ↩

-

ZKAttest - https://eprint.iacr.org/2021/1183 ↩ ↩2

-

Sumcheck - https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/146585.146605 ↩

-

Ligero - https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/1608 ↩ ↩2

-

Random Oracle Model - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Random_oracle ↩

-

Number Theoretic Transform - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discrete_Fourier_transform_over_a_ring#Number-theoretic_transform ↩

-

A security review by Trailsofbits - https://github.com/google/longfellow-zk/blob/main/docs/static/reviews/Longfellow_report_2025_08_18.pdf ↩

-

Project Longfellow with Deutsche Bank: https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/financial-services/deutsche-bank-delivers-ai-powered-financial-research-with-db-lumina/ ↩

-

Noir language: https://noir-lang.org ↩

-

OID4VP specification, Appendix B: https://openid.net/specs/openid-4-verifiable-presentations-1_0.html#appendix-B ↩

-

JWT circuit in Longfellow: https://github.com/google/longfellow-zk/tree/901c856ad9091a1ea6c16de823f3fad4f4b3df19/lib/circuits/jwt ↩

-

Longfellow review by dyne: https://news.dyne.org/longfellow-zero-knowledge-google-zk/ ↩

-

Token Status Lists: https://swiyu-admin-ch.github.io/technology-stack/#credential-revocation–token-status-list ↩