Comparing ZK systems

In this blog post we compare zero-knowledge proof systems with a focus of their usability in digital identity systems.

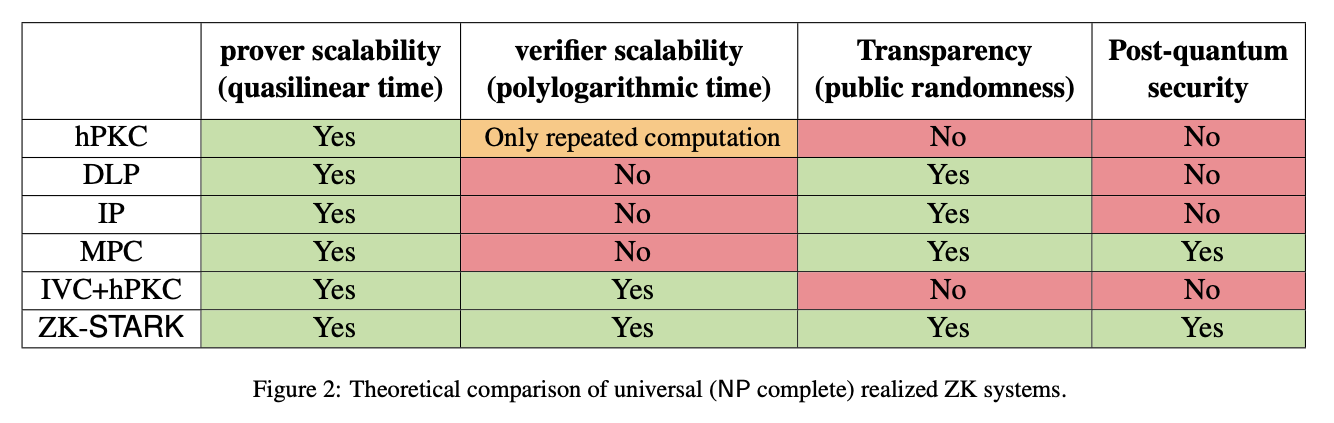

We use the comparison found in “Scalable, transparent, and post-quantum secure computational integrity”1 (2018), Eli Ben-Sasson et al. They present a transparent zero-knowledge proof system named “ZK-STARK”, but their work also includes a comparison to other ZKP systems according to a few criteria.

We extend their comparison with recent work from Google and Microsoft in this domain.

Comparing ZK systems

Here’s the table used to summarize the comparison at page 10 of the STARK paper:

Requirements for digital identity systems

When thinking about digital identity, the most interesting ZK constructs are:

- easy on the prover’s resources – when designing for people’s identity, the provers in ZK interactions are more often than not consumer hardware. It must be quick to prove something in a ZK system

- more lenient with the verifiers – for now, we model verifiers with access to computing power reasonably more powerful than the prover’s (i.e., not LLM-training hardware, but also not portable device hardware)

- transparent – the lower the overhead for global coordination and trust requirements, the better (ideal case)

With regard to post-quantum security, the answer is not clear-cut: Ideally we want the system to be post-quantum safe. Realistically, digital identity systems currently use ECDSA to sign credentials, which is not post-quantum safe. Thus, we consider post-quantum-safety a nice-to-have but not mandatory.

To “public setup” or not

While a transparent system is ideal to avoid additional trusted parties or ceremonies, we must discuss what public setup means for digital identity.

Public setups come in two flavors, borrowing the description from Bulletproofs2 they are either:

- uniformly random

- highly complex CRS

The first one requires deriving randomness using tools such as a hash function and does not require parties to be cautious about intermediary values.

“Highly complex CRS” setups require the use of intermediary values sometimes referred to as toxic waste. The CRS must be generated by an honest party that has to be trusted to forget these toxic values. In case it does not, that party can use the values to forge valid proofs. Groth163 is one example of SNARK requiring such a setup.

In the context of digital identity, and in particular in Switzerland, we assume the party generating the CRS to be the state. In that instance, the CRS generator coincides with the credential issuer, a party that can issue forgeries anyway. As such, we chose to retain systems that require a public setup in our comparison.

Note: alternatively, this setup can take place using MPC, in our context this hardly solves the governance issue. Scalable Multi-party Computation for zk-SNARK Parameters in the Random Beacon Model describes such an approach.

A note on prover’s scalability

It is to be noted that just because prover scalability has a green yes in a table does not imply it is practically feasible to use such a system for zero-knowledge presentation of ECDSA signed credentials. This has to do with the fact that in most public sector digital identity proposals, credentials are required to be signed by the holder using ECDSA. To include this signature in the ZKP, the use of specific mathematical constructs are required, which are very complex to emulate for ZKPs relying on arithmetic circuits.

Some publications use clever constructions to make these computations more efficient: ZKAttest4, and Crescent5 that uses Spartan6 with the Tom-256 curve presented in ZKAttest.

Breakdown of the categories

hPKC - homomorphic Public Key Encryption

In his paper from 2016, Jens Groth mentions

While pairing-based SNARGs are efficient for the verifier, the computational overhead for the prover is still orders of magnitude too high to warrant use in outsourced computation.

Today it looks like Groth163 is still one of the best general-purpose SNARKs in this model. Plonk7 authors evaluate their system as slightly slower (notably for the prover) but it does not require a per-circuit public setup. Clearly, the universality of the circuits themselves is a big factor in choosing a scheme.

DLP - Discrete Logarithm Problem

Systems relying on DLP are not post-quantum safe as Shor’s quantum factoring algorithm can solve DLP efficiently. Except for this, systems like Bulletproofs2 are attractive to build modular proofs with arbitrary computations. The benchmarks published for Bulletproofs show performances linear in the number of multiplication gates in the circuit. But proving knowledge of a SHA256 pre-image is measured at around 19.5 seconds, prohibitively expensive for the purpose of digital credentials.

Another strong proposition relying on DLP is one of the implementations of Spartan8 appropriately dubbed SpartanDL.

IP - Interactive Proof based

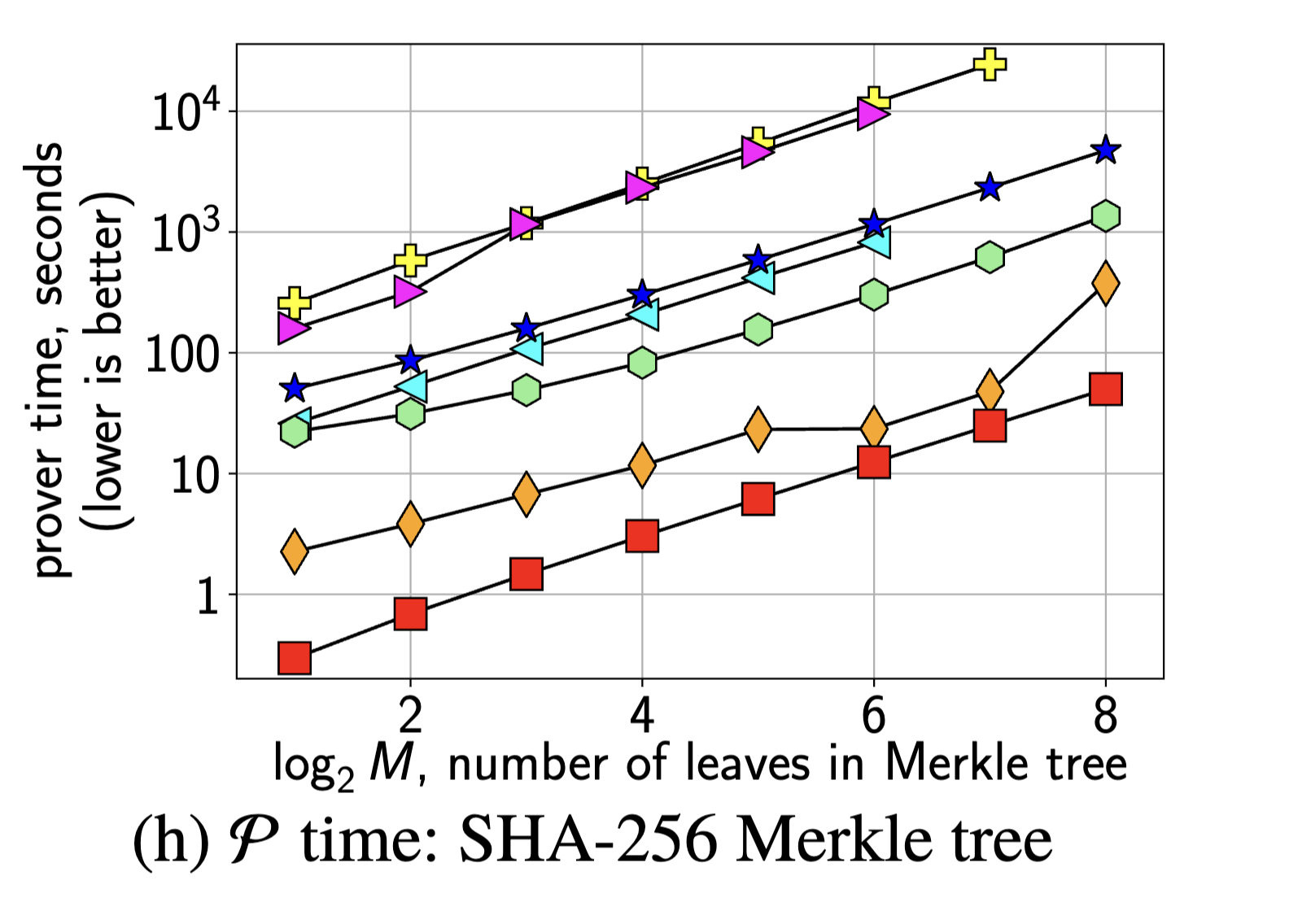

Recent work such as Hyrax9 proposes ZK-IP protocols. Their benchmarks of Hyrax show Ligero10 (see MPC paragraph) to be faster for the plotted values. libSTARK is also high up in prover’s time.

The figures are from Hyrax9, section 8.1 “Comparison with prior work”.

MPC - Secure multi-party Computation

Also called “MPC-in-the-head”, this model builds ZK-PCP proofs based on secure MPC protocols. The most relevant for us here are Ligero, an efficient construction for cryptography-related provers. The Longfellow-zk paper from Google uses it as one of the bases and combines it with sumcheck along with some optimizations to create a proof system that the authors estimate 20x faster than Ligero itself11.

IVC+hPKC - Incrementally Verifiable Computation

This is mostly a technique (as exposed by the authors of STARK) that, applied on top of an hPKC construction, is used to save prover space. We will return to these if this proves necessary with constructions that are prover-time efficient.

ZK-STARK

As all feature comparisons require, ZK-STARK ticks all the boxes in the table. There are caveats however, one of which is formulated by Matteo Frigo and Abhi Shelat in their work on Longfellow11:

The STARK system is a ZK argument system that requires no trusted setup and also produces a smaller proof than other proof systems including Ligero. However, the cost of the smaller proof, as established by many published benchmarks in the literature show that the STARK prover time is larger than the Ligero prover.

The “published benchmarks” are from Alexander Golovnev et al. - Brakedown: Linear-time and field-agnostic snarks for r1cs.

Ligero’s authors make the same statement:

preliminary comparison with the concrete efficiency of our construction suggests that our construction is generally more attractive in terms of prover computation time and also in terms of proof size for smaller circuits (say, of size comparable to a few SHA-256 circuits), whereas the construction from [the ZK-STARK paper] is more attractive in terms of verifier computation time and proof size for larger circuits.

Constructions for digital identity

The following two publications focus on delivering zero-knowledge presentation of existing credentials. That is, one of the primary goals of the authors is to leave existing digital identity infrastructure untouched (i.e.: no change to issuer’s signatures, credential formats) and still enable proving statements about issued credentials in zero-knowledge interactions.

Google’s Longfellow-zk (2024)

As mentioned in the MPC paragraph, Longfellow combines Ligero and Sumcheck in an efficient zero-knowledge proof protocol relying on the same assumptions as Ligero (existence of secure hash functions) and achieving around twenty times the performance. Notably, the authors use their system, along with highly efficient circuit construction, to present mDoc credentials in zero-knowledge interactions taking less than a second on (high-end) consumer phones.

This construction is complete and implemented. The ease or difficulty of adapting it to other credential formats remains to be evaluated.

Microsoft’s Crescent (2025)

Microsoft Research and UC Berkeley published a ZK system for existing credentials named “Crescent”. It is notable because it starts from the same premise as Longfellow (building on top of existing credential and signature schemes), but proceeds very differently. Crescent is very modular but its main part – based on Groth16 – requires a public setup. Crescent suffers from a second drawback: some of the prover’s computations are very time expensive. The authors mitigate this issue by making sure most of this cost can be paid as pre-computation so that live-interactions with verifiers are still fast and reactive enough for human users.

The construction is complete and modular enough that we pay attention to it in the digital identity context despite this drawback.

Takeaway and next steps

Some of the surveyed systems – while theoretically applicable – show prover time that is prohibitively expensive for use with verifiable credentials (e.g., Bulletproofs).

Some would require a more careful analysis of the underlying circuits to be able to gauge the final construction’s performances (Hyrax, Spartan).

- Ligero itself is more attractive for its speed than alternatives such as Hyrax – it is also post-quantum secure, scoring bonus points.

- zk-STARKs themselves have attractive properties but mostly for a specific kind of circuits (sequential work).

- Spartan claims a “prover-optimal” construction, but the fact that Crescent does not use it to build a complete system hints that even a prover-optimal SNARK is not enough to get decent credential presentation times.

- Longfellow has an optimized construction in terms of practical performances and security assumptions.

References

-

STARK - https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/046 ↩

-

Bulletproofs - https://eprint.iacr.org/2017/1066.pdf ↩ ↩2

-

Groth16 - https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/260 ↩ ↩2

-

ZKAttest - https://eprint.iacr.org/2021/1183 ↩

-

Crescent - https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/2013 ↩

-

Spartan - https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/550 ↩

-

Plonk - https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/953 ↩

-

Spartan - https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/550 ↩

-

Hyrax - https://eprint.iacr.org/2017/1132 ↩ ↩2

-

Ligero - https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/1608 ↩

-

Anonymous credentials from ECDSA: https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/2010, see also longfellow-zk: https://github.com/google/longfellow-zk ↩ ↩2